[Korea and the fourth industrial revolution <4-1 Health>] When the cure is slicing DNA, printing organs

Hemophilia, cancer, muscular dystrophy - all diseases deemed incurable are gone in this hypothetical world, where people are split into genetically perfect humans and “invalids” with hereditary disorders.

Twenty years after the cult film imagined a world without genetic diseases, scientists are getting closer to realizing a cure for these rare, unsolved medical conditions through a genome editing technology called CRISPR/Cas9.

Named the “Breakthrough of the Year” by Science magazine in 2015, the technology allows doctors to cut, replace and alter genes with unprecedented ease and accuracy for a relatively cheap cost using an enzyme called Cas9 and a guide RNA that helps the enzyme target the right site. It has the potential to significantly reduce the likelihood of disease recurrence compared to drug treatment.

Klaus Schwab, a German economist who popularized the term fourth industrial revolution, cited genome editing as an integral part of future health care along with bioprinting technology and robots designed for clinical use.

If successfully implemented, CRISPR will not only allow the removal of problematic genes from the human body but could also be used to create “designer babies” born without hereditary disorders, which undoubtedly raises ethical questions.

For now though, universities, research institutes and biotech firms around the world are simply hoping to commercialize the technique for therapeutic purposes, and it is expected to be lucrative. The genome technology market is expected to reach $23 billion in 2022, according to Occams Business Research and Consulting, an Indian consulting firm specializing in the medical field.

In Korea, ToolGen is taking the lead as it is the only company so far to have multiple genome editing technologies including CRISPR.

Kim Jong-moon, the company’s CEO, said ToolGen is developing a CRISPR system aimed at tackling maladies like Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, cancer, hemophilia and age-related macular degeneration.

“The major target of genome editing is genetic disorders that have become prevalent over the past 50 years,” he said.

Affiliates of Korea’s powerful family-run conglomerates are throwing money into a project to jointly develop genomic editing tools. Some of these companies have a personal stake in the investment. The chairman of Samsung Group, Lee Kun-hee, and his nephew Lee Jay-hyun, chairman of CJ Group, suffer from Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, a hereditary neurological disorder that currently has no cure.

Samsung Medical Center, a hospital network owned by Samsung, signed a partnership with ToolGen to develop a gene editing tool for Charcot-Marie-Tooth. In cancer treatment, ToolGen has a deal with Green Cross Cell, a Korean drug maker.

But since ToolGen’s development is in its early stages, sales at the biotech firm only stood at 2 billion won ($1.8 million) last year.

Still, there is promise. Kim Jin-soo, a chemistry professor at Seoul National University, said the application of CRISPR is not confined to resolving hereditary disorders since a vast majority of diseases are caused by genetic mutations.

“In principle, CRISPR/Cas9 can treat any disease caused by flawed genes,” said the professor, a pioneer in gene editing and founder of ToolGen.

Gene editing can also be applied to crop production and animal breeding, Kim added, to grow better crops and breed animals with specific functions.

The professor has in fact successfully engineered a range of enhanced animals and crops including a “double-muscled pig” that has leaner meat and a soybean with high oleic acid content to produce healthier oil.

Global DNA race

Genome editing technology has been around for years, but previous tools couldn’t generate the hype surrounding CRISPR because of their various drawbacks.

“The first-generation tool, the zinc finger, had low accuracy in targeting faulty genes and was expensive,” said Kim Eun-jeong, a researcher at the private think tank LG Economic Research Institute, “while its successor TALENs is hard to insert into cells because of its size.”

CRISPR, on the other hand, has reduced the time for genome editing from several months to several days. The cost has been cut from thousands of dollars to around $30, the researcher said. These characteristics have boosted the technology’s appeal and sparked a high-stakes race around the globe to commercialize it.

A Korean team led by Prof. Kim Jin-soo was one of the first to prove that CRISPR can be used in human cells in 2013, but the country is now lagging behind nations like the United States and China, which are making sizable investments and granting regulatory approval for research. Most gene editing research in Korea is restricted to animal testing.

Leading players in gene editing are based in the United States and Europe and associated with universities, including Editas Medicine, Intellia Therapeutics and CRISPR Therapeutics in Sweden. These three firms, all listed on the Nasdaq stock market in New York, have a wider portfolio than their Korean counterparts, backed by huge investment and licensing deals. Editas Medicine, for example, received $120 million in round-two venture capital funding in 2015 from a group of investors that included Google Ventures, after drawing $43 million in round one.

“North America is the largest geographical market in CRISPR because of the high level of academies and research based in the region,” said a report from Occams Business Research & Consulting.

But in terms of future potential, the Asia region is leading, according to the report.

“The Asia-Pacific region is expected to grow at the fastest rate in the forecasted period due to increase in number of contract research organization and emergence of drug discovery,” it said.

China has set its eyes on being a major regional player. The country is conducting somewhat radical and controversial trials.

Chinese scientists became the first in the world to use CRISPR on humans last year when they injected genetically modified cells into a patient with lung cancer.

The age of artificial organs

Despite the rise of gene editing technology, many doctors still see conventional surgical operation as the primary treatment method in the coming decades because of gene editing’s nascent development stage and ethical issues surrounding the technology.

And there’s plenty of innovation going on in the realm of surgery. For example, 3-D printing technology is finding its way into hospitals with artificial skin, bones and even tissues for research or transplant being fabricated from 3-D printers.

As so-called bioprinting technology is growing more sophisticated, the market is expected to expand, reaching an estimated $1.82 billion by 2022, according to a report by Grand View Research, a U.S. consulting firm.

In response, a handful of Korean start-ups and hospitals are venturing into this new technology.

MEDICALIP, an in-house medical start-up at Seoul National University Hospital, developed an artificial liver made of silicon using 3-D printing.

Park Sang-joon, head of the start-up and a professor at the hospital, said the success rate of excising cancer cells in the liver increased to 98.8 percent from 85 percent when doctors conducted trial operations with the artificial liver.

Another start-up, Rokit, has developed a printer to generate organs. The material it uses can force cells to interact and form new functional tissue. The company says it plans to export the product worldwide.

But to increase demand for artificial organs, just mimicking the exterior is not enough. They will need to have the same functions and change property over time in the way human organs do. A majority of local start-ups have yet to reach that level of sophistication.

One U.S. company, Organovo, has made a printer that can produce cells which undergo cellular senescence and death, much as they would in living human tissue.

Smart rehabilitation

Another clinical area that could be facilitated by advanced technologies is rehabilitation. In a rapidly aging society like Korea’s, the demand for robots to help people walk and move will likely grow.

The rehabilitation robot market’s size stood at $233 million in 2014, but it’s expected to jump to $1.1 billion in 2021, a whopping 472 percent increase, according to market tracker Research and Markets.

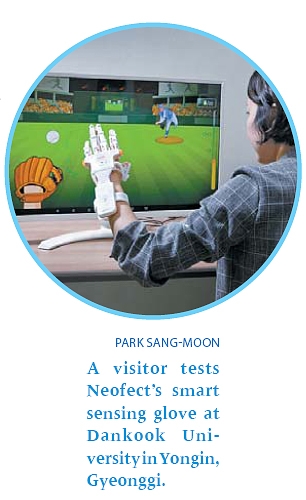

Neofect, a medical start-up, has combined entertainment and technology to help people who suffer from neurological disorders and stroke restore movement in their body. It has created a glove fitted with bending sensors that can be hooked up to Neofact’s software platform, where users can play sports and arcade games, kind of like a Nintendo Wii.

“My father and uncle suffered strokes, so after learning gamification techniques, artificial intelligence and sensing, I thought it would be great if I could apply them to help stroke patients rehabilitate better,” said Ban Ho-young, CEO of Neofect.

The National Rehabilitation Hospital in Korea has conducted clinical research using the smart glove and says it has shown better clinical outcomes than conventional therapy for stroke patients. The product has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and people can rent it there for $99 a month.

But Neofact’s entry into the United States means there are several other companies hot on its tail. Well-known players include AlterG and Kinetic Muscles, both U.S. manufacturers, and Hocoma, a Swiss company.

“The global rehabilitation robotics market is highly competitive, with the presence of numerous global and regional players offering a wide variety of robotic therapies depending on their medical application,” Research and Markets said.

Despite the challenges, Ban said the company will expand the range of its products to serve different body parts, with an annual sales target of 10 billion won.

The company posted 2 billion won in revenue last year.

BY PARK EUN-JEE [park.eunjee@joongang.co.kr]

with the Korea JoongAng Daily

To write comments, please log in to one of the accounts.

Standards Board Policy (0/250자)