[Korea and the fourth industrial revolution <10-1 Finance>] Need investment advice? Call a robot

[BAE MIN-HO]

One lady goes up to the machine and asks Alpha, the robot’s name, whether it’s eaten lunch yet, a common greeting in Korea.

Alpha turns its head toward the woman and playfully responds, “Don’t dare to ask unless you’re buying.”

The lady chuckles and then asks Alpha for the latest stock market numbers.

The interaction might seem contrived, but the gimmick belies the machine’s true power: the ability to recommend financial products based on the users’ investment appetite. Alpha asks investors three questions about the amount of risk they’re willing to take and their preferred type of investment, and based on the answers, the robot can generate a list of recommended funds for the client.

Alpha is a prime example of where Korea’s financial industry is heading. Digital tools and apps on smartphones and computers are now providing financial advice, portfolio management and real-time analysis of markets. In February last year, the Financial Services Commission, Korea’s financial regulatory agency, approved the use of so-called robo advisers, paving the way for the commercialization of automated investment services.

Woori Bank staff demonstrate its robo adviser, Alpha, at its branch in Myeong-dong, central Seoul, on June 13. [PARK SANG-MOON]

“When we look at the case of the United States, where the industry is booming, clients can enjoy advisory services for less than 0.5 percent,” said Park Seon-hoo, a researcher at IBK Economic Research Institute. “Money managers at major banks and securities companies currently charge at least 1 percent.”

Park believes robo advisers will likely draw Korean millennials, the demographic cohort born between 1980 and 2000, as they have in the United States. Another target client base is the upper middle class whose net assets range from 100 million won ($88,000) to 1 billion won, and even lower than 100 million won. This group could become underserved as legacy investment companies focus on wealthier clients.

“Private bankers will be able to give time for consultation when a potential client has at least 600 million won,” said Choi Byung-gil, director at Fount Investment, a robo adviser company. “But we are looking at broader, younger clients who might have fewer assets but potential to grow. Our vision is to serve customers who maintain assets as low as 100,000 won per month.”

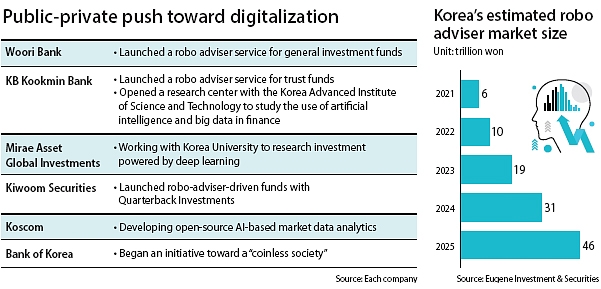

There are currently 12 funds in Korea run by robo advisers, according to the Korea Financial Investment Association, which represents the country’s financial industry. The asset size is estimated to be around 200 billion won. Although the figure pales in comparison to more mature markets like the United States, Korea appears to be on a fair track given the service is only a year old. Eugene Investment & Securities predicts Korea’s market growth will flat-line through 2020 but rise to 6 trillion won in 2021 and 46 trillion won in 2025.

For the beginning phase, leading banks and securities companies have opted to sign partnerships with robo advising firms like Quarterback Investments, December & Company and Fount to test algorithms and platforms. Quarterback is working with KB Kookmin Bank and Kiwoom Securities, and December & Company has joined with NH-Amundi Asset Management.

“Robo advisers can craft portfolios and manage funds based on quantitative analysis and are more objective than their human counterparts,” said Lee Seung-jun, chief strategy officer and director of investment at Quarterback Investments, the oldest and largest robo adviser firm in Korea.

When the giants come marching

Major Korean firms like Mirae Asset Global Investments, KB Asset Management and Samsung Securities are eyeing moves into algorithm-based wealth management, and when they throw their hats in the ring, the market for robo advisers will likely experience significant growth. The three firms earlier this year either launched robo adviser-driven funds or applied to participate in a test system run by the Financial Services Commission.

In the United States, small automated investment service firms like Betterment and Wealthfront were the kindling that drove the industry’s early-stage growth in the 2000s, but it was the entry of industry giants like Charles Schwab, Fidelity and Vanguard that contributed to increased access to robo advisers, and now these big players dominate the market.

The amount of assets under management by robo advisers in the United States is now $224.8 billion, according to market tracker Statista, with an annual growth projection of 47.5 percent through 2021. Many of them focus on a diversified mix of exchange-traded funds at different risk levels.

Despite the promise, firms complain strong regulations are hampering the industry’s growth. Presently, automated investment cannot be done completely online since clients still have to visit the offices of securities companies and speak face-to-face with fund managers for the initial sign-up.

Lee Seung-jun of Quarterback Investments argues that the rule prevents service providers from significantly lowering their fees since human guidance requires cost. “We can’t charge the same commission rates as in the U.S. because we are not allowed to reduce costs through digitization,” he said.

Lee declined to specify how much commission his company charged, though he said it was “in line with or slightly lower than existing asset management firms.”

Fees at Korea’s 12 robo adviser funds range from 0.6 to 1.3 percent, according to the Korea Financial Investment Association.

A source at the Financial Services Commission said the government agency wants to foster the robo adviser market but hasn’t decided whether to lift the regulation requiring human advisers. “The Financial Services Commission acknowledges that non-face-to-face transactions are an irreversible trend,” the source said.

Limits of the robotic touch

Financial authorities aren’t the only ones cautious about automated wealth management. Investors are, too, as reflected by the modest size of assets handled by robo advisers in Korea. The lack of reliability and impressive returns has been considered a weak point for the technology. Last month, the country’s robo funds only made an average 0.86 percent return on investment, according to the Korea Financial Investment Association.

But analysts like to point to more fundamental downsides of machine-led investment, namely the lack of human touch and inability to comprehend diverse goals at different stages of life.

“Robo advisers are unable to provide more diverse and multilayered financial consulting such as retirement plans and predicting the value of asset prices in the future,” said Seo Bo-ick, a researcher at Eugene Investment & Securities.

In a survey of 2,530 people in January, 34 percent of respondents said they were not willing to use robo advisers, according to the Korea Financial Investors Protection Foundation, a consumer rights group. Only 18.9 percent said that they would consult with a robot, while the remaining 41 percent remained neutral.

The skeptics cited reliability as the biggest factor for foregoing the new technology. They argued that human needs are too complex for a simple paint-by-number approach that most robo advisers right now can provide.

This is precisely why firms in the United States that specialize in robo advising still complement their automated investment services with human consultations. Betterment, for example, has two additional tiers of service that provide regular advice from financial planning experts.

Other analysts see risk in robo adivsers’ susceptibility to technical glitches and hacks. “There is also no clear legal protection for those affected by cases where robo advisers don’t perform as intended,” said Lee Hyo-seob, a researcher at the Korea Capital Market Institute.

The Financial Services Commission and industry players have played down the negatives, saying test bed platforms are designed to filter out any underperforming algorithms.

Concerns about mass layoffs, especially of human financial advisers, will also likely get in the way of widespread adoption of robo advisers in Korea. There’s precedent for such concerns: BlackRock, the world’s largest fund management company, has removed at least seven portfolio managers from their current assignments, and the Royal Bank of Scotland said it plans to replace 220 investment staff members with robo advisors.

In Korea, the number of employees in the securities industry has been on a constant decline since 2011, falling 19 percent to 35,699 as of the end of last year, and observers predict the broader application of automated investment services will exacerbate the trend.

Crunching the numbers

Asset managers are not alone in potentially losing their jobs to digital equivalents - financial analysts are feeling threatened by analytical software capable of parsing through large amounts of data in a matter of minutes.

Let’s take the impact of North Korea’s missile tests on the financial markets as an example. If one wants to calculate the exact numeric correlation between North Korea’s posturing and changes on the Kospi, currencies, bonds and commodities over the past 30 years, it would take at least several days or even weeks, a process that would require a combination of Bloomberg codes, Google searches and Excel spreadsheets.

An algorithm could do the work in about five minutes.

There are many start-ups developing this type of analytical software - one of the biggest is Kensho, which has received investment from Goldman Sachs. The U.S.-based start-up’s flagship platform, Warren (named after Warren Buffett), can instantly answer millions of complex financial questions and even create sophisticated financial models.

Koscom, a Korean government-run financial IT solutions company, envisions a landscape where market participants and the public can access such platforms. It announced earlier this year that it is working on a financial market analysis system based on artificial intelligence. It hopes to begin by providing analytical reports on certain stocks written by robots.

Another Korean company, Uberple, hopes to be the native answer to Kensho. Founded in 2013, the Seoul-based start-up built a platform called Snek that can analyze various data sets including news articles, analyst reports, corporate electronic disclosures and government announcements. The company plans to install a search engine called DeepSearch to perform keyword-based queries.

“Current financial analysis offers limited perspectives,” said Joo Eun-hwan, a manager at Uberple. “But we try to provide broader, user-oriented data analysis that allows investors to find a correlation between certain events and financial market movements using the quants.”

BY PARK EUN-JEE [park.eunjee@joonang.co.kr]

with the Korea JoongAng Daily

To write comments, please log in to one of the accounts.

Standards Board Policy (0/250자)